Stories 'From Away' - The Alchemy of Mangoes and Memory

During the pandemic, I was transfixed by a series of short documentaries sharing food stories of grandmothers around the world, filmed by their grandchildren. Each vignette of “Grandma’s Project” was both completely foreign to me and totally familiar. Filmed in places I had never been, in languages I didn’t understand — grandmothers making Moskva Torta in Moscow, Tortilla de Patates in Spain, Molokheya in Egypt. What surprising feelings these little films stirred up! This must be my own grandmother, my own mother — wearing the same sensible shoes, an apron over her Sunday dress, a twinkle in her eye. Her sweet low chuckle as she mixed and tested and pulled dishes from the oven.

I was reminded of “Grandma’s Project” when I sat down for tea with Margaret Boyle and Concepta Jones, along with Stephanie Dunahy, who has invited both women to teach workshops at “Now You’re Cooking,” the beloved kitchen shop in downtown Bath. Concepta and Margaret have in common at least three things. Both have “hyphenated identities” — Mexican-Jewish-American in Margaret’s case, South African-Indian-American in Concepta’s. Both appreciate food as a connector of communities. And both trace their earliest food memories to earlier generations of women. Margaret uses the Hebrew expression “l’dor v’dor” to describe this inheritance.

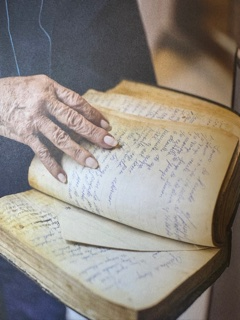

How true that many of us learn our family stories from “the most knowledgable authorities — the women who knew how to cook,” writes Margaret in Sabor Judio, a cookbook co-authored with Ivan Stavans that shares traditions passed down to them by their Mexican-Jewish grandmothers and great grandmothers. Margaret is the Director of Latin American, Caribbean and Latin Studies at Bowdoin College and associate professor of Romance languages and Literatures. Among the source materials for her cookbook are carefully detailed notebooks that have preserved, documented, and revised family recipes over the years in a mix of Spanish, Hebrew and English. The noted instructions are imprecise at best; Margaret calls it “a secret that travels through generations” that everyone measures ingredients in different ways — a handful of rice, a bit of oil, a sprinkle vinegar.

Margaret’s food story begins in 1920, when, at the height of violent attacks on Jewish communities in Eastern Europe, Margaret’s great-grandmother Malka Poplawski left Poland at the age of 19 to travel alone to Cordoba, Mexico. She married a man she had never met, who also still had family in Poland. They were strangers, but spoke the same language. They upheld the same traditions, including a kosher kitchen and a weekly Shabbat meal. They settled in a community with other immigrants from Eastern Europe, setting up a general store to supply neighbors with provisions from home. Margaret imagines her great grandmother as a young women — what it was like to leave siblings and parents behind, what she might have brought with her and what she left behind, and the necessity of reinvention and preservation to her very survival.

Margaret herself was raised in Los Angeles in a large, extended Jewish Mexican family. Her maternal grandparents lived a block away. It was a time of “luncheando y platicando” — “lunching and schmoozing,” with food in abundance. Margaret recalls the flavors of squash blossom quesadillas, mango jicama salad, brisket and rhubarb. “Un poquito mas?” was a common refrain. When her great grandmother visited from Mexico City, her suitcase would be filled with loaves of Chocolate Babka, wrapped in foil to be saved and eaten between her visits. Malka lived in an apartment in Mexico City, which Margaret remembers as a dizzying place of massive grocery stores and vibrant street markets. Malka spoke only Spanish and Yiddish. Margaret knew neither language. But as she followed Baba Malka through the market stands, as Baba picked mangoes with a little give to them, a sweet fragrance, they understood each other completely. And on occasions when they returned to the apartment from market with a live chicken in hand, the explanation hung between them unspoken when the squawking chicken was whisked away through a doorway to an unknown part of the building, to later reappear — far more subdued — as the main dish on the dinner table.

Margaret didn’t feel the acuteness of her identities until she left her family and community in Los Angeles. Arriving in Maine, where ingredients like matzah were not readily available in grocery stores, she still found ways to make the meals of her childhood table. She kept a pantry inspired by her grandmother’s, filled with jams and preserves, pickled herring, and fresh cheese. Adapting to the climate in Maine, Margaret’s jams are made from peaches from her own trees. When she cooks for family and friends, they tend to linger at the table, honoring the idea of “sobremesa” — of sharing and connecting over food. Always singing, stories, and games at Margaret’s table, and always dessert.

Concepta grew up 10,000 miles away from Margaret’s home in Los Angeles. Concepta’s great-great-grandparents arrived in the late 1800s by steam ship to Durban, South Africa, among the indentured Indians who provided labor for British sugar plantations there. It was a difficult life where the work of cutting the thick stalks of cane plants, removing the leafy tops, and chopping the cane into smaller pieces was relentless. In a new land where little was familiar, the Indian community adapted what was available to recreate the foods they missed from home. Maize became a rice substitute. Indian vegetables were grown from seeds that had been carefully carried on the long voyage. The unique spice blends that would become foundational to “Durban curry” took hold.

Concepta’s father was East Indian, her mother South African. (“A long story” Concepta tells me.) Growing up in South Africa at the height of apartheid, Concepta learned to cook not as an outlet for creativity — that would come later — but out of necessity. At the age of seven, Concepta knew that learning to prep curry or grind ginger with a mortar and pestle were life lessons in self sufficiency. Like Margaret, Concepta recalls the sights and sounds of markets, of buying live chickens from a truck and preparing them, with all that involved. Of mangoes piled high in baskets, a promise of sweetness to balance the spicy curries with which they would share a plate. Homes in Concepta’s community — segregated during apartheid — were close together, creating a “comforting hum of family life and community.” In the afternoons, Concepta would join her brothers for hide and seek or street tennis, using chalk to mark the court, and handmade racquets. Occasionally the games would pause to allow a car to roll through. Her mother was not a quiet cook — the sounds of a metal spoon scraping the sides of the pan, the sizzling of hot oil, the smells of cumin, coriander, and chili powder — these were the signs that dinner would soon be on the table, calling the children home.

Concepta found herself in New York, a young woman freshly married. The city was “always in motion, always demanding.” She describes these years as “a mixture of struggle, pain and perseverance.” Concepta called on the skills of self-reliance and survival that had been formative in her childhood. Her church community helped her through the hardest times. As her great-great-grandparents had done three generations earlier, Concepta made do on her own, including in the kitchen. With all of the knowledge, but none of the familiar ingredients available, Concepta set about creating her own spice blends for the dishes of curry and rice that reminded her of home.

Those spices turned into a business that today includes hot “ready to eat” curries sold at the United Farmer's Market of Belfast and regular cooking classes for those who want to make dishes from scratch. When Concepta cooks for church dinners, for friends and neighbors, it is going to be a “big do — hospitality is a huge thing with Indians.” Which brings me to my new obsession — Concepta’s driveway in Waldo, home to a self serve bakery cart stocked with cardamom cookies, fennel loaf, and garlic cilantro bread. This is the alchemy of cultures aligning — the concept of “self serve” food stands are such a lovely part of the vibe in Midcoast Maine, the flavors of the bakery cart are so gorgeously “from away.”

Margaret and Concepta agree that isn’t easy being “from away” in Maine, but Concepta’s pronouncement that “people welcome this kind of culture and color” is backed up as much as the waiting list for the workshops at Now You’re Cooking. It seems we all want to be in the kitchen with Margaret when she makes tomatillo salsa, chipotle matzah ball soup, and lime macaroons. We have to register early to learn Concepta’s secrets to the South African Indian street food Bunny Chow — a hollowed-out bread loaf filled with spiced curry.

We riff on the idea of a South African-Indian-Jewish-Mexican dinner party, a table piled high with chicken and mango, salsas and spices. Around the table we would share songs and stories, our mothers, grandmothers, and great grandmothers there with us in person or in spirit. “A big do,” as Concepta would say.

Margaret’s Mango Kugel

Boil a pound of wide egg noodles and set aside to cool. Peel and chop one medium ripe mango and 3 medium apples. Mix together 7 large eggs, lightly beaten, along with 16 ounces of cottage cheese, half a stick of melted butter, 3/4 cups of light brown sugar, and a bit of brown sugar and salt. Stir in the noodles and fold in the mango and apples. Pour into a buttered baking dish and bake at 350 degrees until the kugel has set and the top is golden brown (45 - 60 minutes). Serve warm or at room temperature with Concepta’s Durban Lamb Curry (recipe available at iConcepta.com).

Elsewhere in Midcoast Maine, Margaret and Concepta recommend Luchador Tacos in Paris, La Tienda Latina and Masala Mahal in Portland, and Ben Reuben’s Knishery.