Local man's 50-year-long search for answers continues

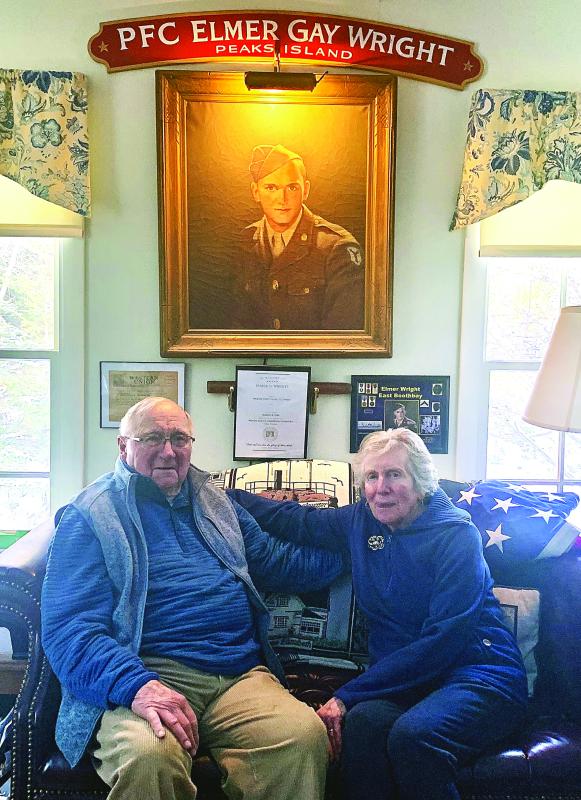

Howard Wright, 95, and wife Dorothy, who has been by his side every step of the way as he investigates the circumstances around his brother's death. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Howard Wright, 95, and wife Dorothy, who has been by his side every step of the way as he investigates the circumstances around his brother's death. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

The original 1944 Purple Heart and some of the new medals awarded posthumously to Elmer Wright for his service in WWII. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

The original 1944 Purple Heart and some of the new medals awarded posthumously to Elmer Wright for his service in WWII. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

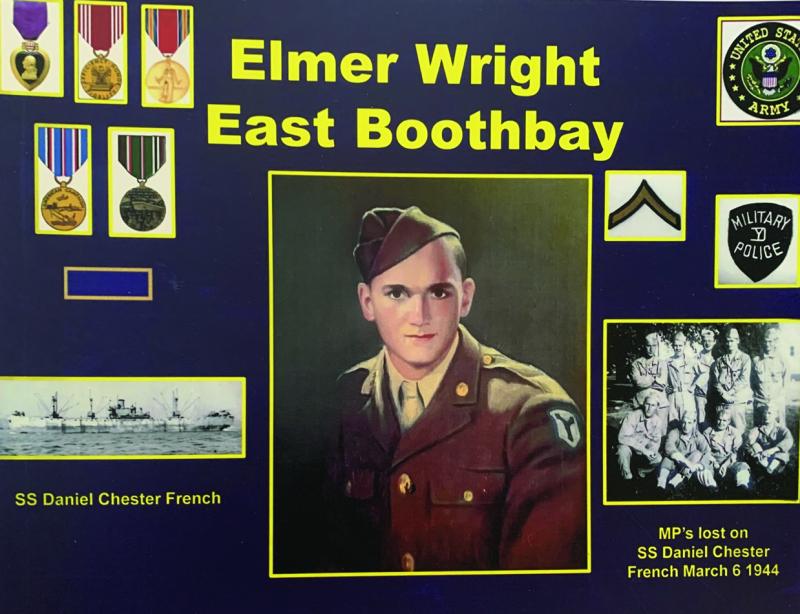

A composite of Elmer Wright's military service.

A composite of Elmer Wright's military service.

Howard Wright, 95, and wife Dorothy, who has been by his side every step of the way as he investigates the circumstances around his brother's death. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Howard Wright, 95, and wife Dorothy, who has been by his side every step of the way as he investigates the circumstances around his brother's death. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

The original 1944 Purple Heart and some of the new medals awarded posthumously to Elmer Wright for his service in WWII. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

The original 1944 Purple Heart and some of the new medals awarded posthumously to Elmer Wright for his service in WWII. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

A composite of Elmer Wright's military service.

A composite of Elmer Wright's military service.

Howard Wright was in eighth grade when the Western Union boy came to the front door of his Pennsylvania home and quietly handed him a telegram. It could only mean one thing. His older brother, Private First Class Elmer Gay Wright, a.k.a “Pat,” was either missing in action or gone.

Originally reported as MIA, the dreaded news that the 23-year-old Elmer had been killed when his ship sank off the coast of Tunisia arrived about a month later. Wright’s father came to him with a simple message: “No more Pat.” And that was that.

When Wright decided to research the German submarine he had assumed was responsible, it was revealed Elmer wasn’t killed by enemy action. Instead, a series of blunders resulted in his boat's crossing into Allied minefields. Wright, 95, now lives in East Boothbay. He has spent the last 50 years piecing together the events from documents, letters and survivor accounts. Among the questions that have spurred on his investigation: What was his brother’s mission?

Unlikely service

Like many young people during World War II, Elmer Wright felt compelled to enlist alongside his friends. One problem: The Navy refused to take him because he was hearing impaired. According to Howard Wright, a bout of whooping cough as a child damaged both Elmer and their sister's hearing, and killed their 3-month-old little brother. Wright believes his death explains Elmer’s protectiveness over him when he was born six years later. “He really looked out for me, watched over me,” he said.

When Elmer was eventually drafted into the Army, he was conscripted for “limited service” away from combat zones due to his disability. But the Army saw value in his linguistic skills. He could lipread English and speak three additional languages. He was transferred to join a nine-person group of other college-educated men for special Military Police (MP) training at Fort Cluster in Michigan, according to Wright.

While there in July 1943, Elmer sent a letter to Howard, who was spending his summer at a camp on Sebago Lake. Elmer describes lessons in marksmanship, criminal investigation, operating explosives, and hand-to-hand combat, all the markers of active military training.

‘Sheer panic’

The troubles began after nightfall on March 5, 1944, for the convoy of 90 ships heading to Iran, among them the Liberty ships (cargo vessels) the Virginia Dare, and Elmer’s ship the Daniel Chester French. It was around 11: 30 p.m. when word came down from the commodore. Change formation. The orders were carried out in “radio silence” with orders flashing out from signal lamps, said Wright.

The morning found the convoy in confusion, stretched across 12 miles. The two Liberty ships were four miles behind the bulk of the convoy. The rough seas that had begun the night before continued. The Virginia Dare was the first to hit the allied minefields at 7:15 a.m. but was able to beach safely with no loss of life.

The Daniel Chester French, full of ammunition, was not so lucky. The 87 Army personnel aboard scrambled to the six lifeboats, which survivors reported were “not enough to accommodate them,” according to official documents. No crew members appeared to help lower them as the unit had been promised. There was no one to tell them about the drains in the bottom that needed to be plugged before launching.

Lt. James Boyle, one of the survivors, later wrote to the Wrights about their son’s final moments. Boyle and Elmer swam to the same lifeboat. While Elmer was frightened like everyone else, he did not let that paralyze him, and “kept his head,” Boyle wrote. Elmer took off his helmet, trying to combat the water rushing into the vessel from the unseen drain.

“(It must have been) like taking a tea cup and trying to bail a full tub of water,” said Wright.

Ten minutes later, a wave lifted the boat and Elmer was gone. He was one of the 37 casualties.

“During the time I knew him, he was always a gentleman, and in the boat he acted like a man,” wrote Boyle.

For many years, the Wright family only had the Purple Heart for Elmer’s service. Wright, with the help of Sen.Susan Collins’ office, was able to secure additional medals for his brother this year, including the Presidental Unit Citation, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with one Bronze Service Star, Army Good Conduct Medal and an American Campaign Medal. A World War II Victory Medal was also awarded in September 2024.

Wright is thankful for the medals, describing them as “long overdue.” Yet, there is still no closure, partly because his brother’s remains were never found. In Tunisia, the North Africa American Cemetery for WWII personnel is filled with white crosses to signify those who have been identified and recovered. Elmer’s is one of the almost 4,000 names on the Wall of the Missing.

Wright explained that recovery missions after sinkings often don’t bother with “floaters” unless they show some signs of life, so there is a possibility that some are conscious but too weak to signal. He tapped his chest, voice trembling. “My brother just was a floater.”

Wright shares the same hopes as his mother, Dorothy Wright, who penned a 1947 letter to the Army mourning her son’s loss: “I can only hope that he wasn’t stunned ... and regained consciousness miles away from any help.”

Wright added, “I mean, just to be left alone out in the ocean; 23 years old, just turned 23.”

Lingering questions

Wright may never know the true nature of his brother’s mission as many files have been lost to time, and facility fires. Relatives of survivors have alluded to the secretive nature of the trip, including interactions with Allied and Axis spies. Wright also has his own theories. Elmer’s French skills would have been useful in French-occupied North Africa. Perhaps his brother’s small, educated unit was meant to help stabilize recently occupied regions?

Nevertheless, Wright still finds other things to spur him on. His current points of interest include seeing if the convoy commodore received a censure for his actions, which were heavily criticized by survivors, and looking more into his brother’s status as an MP from new documents from Collins’ office.

But for Wright, the most important part is preserving his brother’s legacy for Wright's son and grandchildren. “When you go, you go. Now if people can still talk about you, you’re still alive in one way,” he said.