Heartwood’s ‘Eurydice’: Mythic magic

Eurydice (Gina D’Arco) arrives in Hades. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Eurydice (Gina D’Arco) arrives in Hades. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

The Stones - Mary Boothby, Thalia Eddyblouin and Joe Lugosch. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

The Stones - Mary Boothby, Thalia Eddyblouin and Joe Lugosch. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Father (Clifford Blake) tells stories to his daughter Eurydice (Gina D’Arco) to make her remember her life. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Father (Clifford Blake) tells stories to his daughter Eurydice (Gina D’Arco) to make her remember her life. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

A bereft Orpheus tries yet again to communicate with his love, though dead. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

A bereft Orpheus tries yet again to communicate with his love, though dead. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Father makes his daughter a room where there are no rooms. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Father makes his daughter a room where there are no rooms. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Eurydice trying to figure out what to do with a letter. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Eurydice trying to figure out what to do with a letter. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Will Orpheus and Eurydice find their way back to one another? LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Will Orpheus and Eurydice find their way back to one another? LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Orpheus sends a book to his love - or so he hopes. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Orpheus sends a book to his love - or so he hopes. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Putting a ring on it: Orpheus and Eurydice are engaged. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Putting a ring on it: Orpheus and Eurydice are engaged. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Leading characters, from left: Orpheus (Austin Olive), Eurydice (Gina D'Arco) and Eurydice's Father (Cliff Blake) in Heartwood Theater's production of "Eurydice," by Sarah Ruhl. Courtesy of Jenny Mayher

Leading characters, from left: Orpheus (Austin Olive), Eurydice (Gina D'Arco) and Eurydice's Father (Cliff Blake) in Heartwood Theater's production of "Eurydice," by Sarah Ruhl. Courtesy of Jenny Mayher

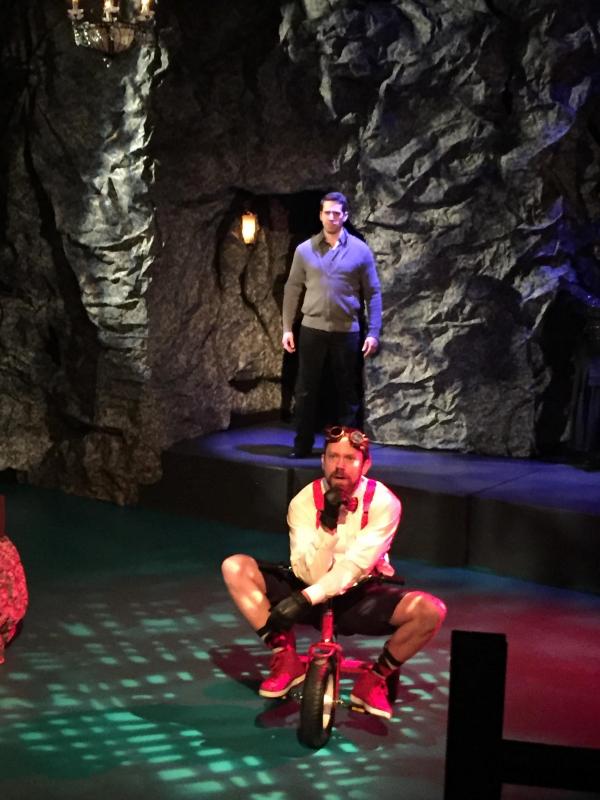

On the set of Heartwood's "Eurydice," Loud Stone (Thalia Eddyblouin), Nasty Interesting Man / Child (Steve Shema) and Little Stone (Mary Boothby). Missing from photo - Joe Lugosch. Courtesy of Jenny Mayher

On the set of Heartwood's "Eurydice," Loud Stone (Thalia Eddyblouin), Nasty Interesting Man / Child (Steve Shema) and Little Stone (Mary Boothby). Missing from photo - Joe Lugosch. Courtesy of Jenny Mayher

Eurydice (Gina D’Arco) arrives in Hades. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Eurydice (Gina D’Arco) arrives in Hades. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

The Stones - Mary Boothby, Thalia Eddyblouin and Joe Lugosch. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

The Stones - Mary Boothby, Thalia Eddyblouin and Joe Lugosch. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Father (Clifford Blake) tells stories to his daughter Eurydice (Gina D’Arco) to make her remember her life. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Father (Clifford Blake) tells stories to his daughter Eurydice (Gina D’Arco) to make her remember her life. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

A bereft Orpheus tries yet again to communicate with his love, though dead. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

A bereft Orpheus tries yet again to communicate with his love, though dead. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Father makes his daughter a room where there are no rooms. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Father makes his daughter a room where there are no rooms. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Eurydice trying to figure out what to do with a letter. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Eurydice trying to figure out what to do with a letter. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Will Orpheus and Eurydice find their way back to one another? LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Will Orpheus and Eurydice find their way back to one another? LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Orpheus sends a book to his love - or so he hopes. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Orpheus sends a book to his love - or so he hopes. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Putting a ring on it: Orpheus and Eurydice are engaged. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Putting a ring on it: Orpheus and Eurydice are engaged. LISA KRISTOFF/Boothbay Register

Leading characters, from left: Orpheus (Austin Olive), Eurydice (Gina D'Arco) and Eurydice's Father (Cliff Blake) in Heartwood Theater's production of "Eurydice," by Sarah Ruhl. Courtesy of Jenny Mayher

Leading characters, from left: Orpheus (Austin Olive), Eurydice (Gina D'Arco) and Eurydice's Father (Cliff Blake) in Heartwood Theater's production of "Eurydice," by Sarah Ruhl. Courtesy of Jenny Mayher

On the set of Heartwood's "Eurydice," Loud Stone (Thalia Eddyblouin), Nasty Interesting Man / Child (Steve Shema) and Little Stone (Mary Boothby). Missing from photo - Joe Lugosch. Courtesy of Jenny Mayher

On the set of Heartwood's "Eurydice," Loud Stone (Thalia Eddyblouin), Nasty Interesting Man / Child (Steve Shema) and Little Stone (Mary Boothby). Missing from photo - Joe Lugosch. Courtesy of Jenny Mayher

“Eurydice” … it’s all about love: the unconditional, unwavering love of a father for his daughter, the love of a daughter for her father, or the love of a woman for a man. It’s about the indelible depth such great love has on our souls - and the lengths we are willing to go to keep that love.

If you’re not up on Greek legends, here’s a brief synopsis of the original tragic tale of Orpheus and Eurydice: Apollo gave his son Orpheus a lute. Orpheus’ God-given (couldn’t resist) ear for music made him the most gifted of musicians; all creatures and the inanimate (rocks, trees) reacted to the melodies. Orpheus fell in love with the beautiful nymph Eurydice and the two became inseparable. Shortly after they wed, their happiness was shattered when Eurydice was bitten by a snake and went to the Underworld ruled by Hades and Persephone. Orpheus, desperate to be reunited with his love, travels there playing the most haunting, melancholy music that affects the gods below. Hades gives Orpheus a chance to reunite with Eurydice, but he cannot look back at her as they travel separately to the land of the living. Impatient to see her again, Orpheus does look back and Eurydice returns to the Underworld.

Heartwood’s fully staged “Eurydice” (yoo-rid-uh-see-uh) is Sarah Ruhl’s modern take on the Orphean myth told from Eurydice’s perspective. In this version, in the Underworld, Eurydice’s deceased father is a major character, and it is ruled by the child, Hades. The River of Forgetfulness, one of the five rivers in Hades, figures prominently; the dead drink from its waters to forget their human lives.

The spot-on performances of this cast and the inventive set design and special effects draw you into the story from start to finish. This play is all about the words that are as charming as one might imagine the music Orpheus composed; poetic, imagery-filled and romantic. The Poe Theater adds an intimacy between the actors and the audience, providing a lovely dimension to the entire experience.

Now to the play. When you first meet Orpheus, played by Austin Olive, and Eurydice, Gina D’Arco, the young lovers are on a beach, flirting, teasing ... kissing. Olive and D’Arco convey their characters’ affection with such genuine feeling that for a minute or two you might think they are really in love. In true romantic form, Orpheus tells Eurydice (through gestures, not words), that the sky, moon, stars and seas belong to her. Now and again, Orpheus drifts off, carried away by the music constantly being composed in his head. Eurydice is the lover of words and books and ideas. She wants to talk about what she’s read and the interesting arguments presented on the pages, or about the new philosophical system she’s been thinking about involving … hats.

Orpheus tells her he has composed a song for her and Eurydice asks him to sing it for her. He declines because it has too many parts — 11 so far — and he’s working on the last. But he hums a melody and tells her to repeat it back to him. She does, and he playfully tells her it wasn’t bad, but her rhythm’s a bit off.

Orpheus asks her to promise she will never forget that melody — even under water (they are going for a swim and then there’s that river I mentioned earlier). Before they go in for that swim, he ties a piece of string around the ring finger of her left hand so she won’t forget. And, yes, that is also Orpheus’ way of asking Eurydice to marry him. An example of the language I mentioned earlier is spoken by Eurydice: “This is what it is to love an artist: The moon is always rising above your house. The houses of your neighbors look dull and lacking in moonlight. But he is always going away from you. Inside his head there is always something more beautiful.”

We meet Eurydice’s father, played by Clifford Blake, in the Underworld, a cave-like atmosphere with the intermittent sound of dripping water, you cannot help but notice the three actors portraying Three Stones, a stone chorus, Little Stone (Mary Boothby), Loud Stone (Thalia Eddyblouin) and Large Stone (Joe Lugosch), based on Cerebus, the three-headed guard dog of the Underworld. The stones are enforcers of the do’s and don’t’s there. (And their late 18th century garb is cool and chic!)

Father has written a letter to his daughter on her wedding day. He is one of the few dead that remember how to read and write. This is a most poignant moment, delivered without pretense, by Blake. It is the first of many emotionally charged moments in the play, but that’s the nature of love, is it not? Father reads it aloud, as though he were making his speech at the wedding reception, he says Orpheus seems like a nice young man, although the fact that he’s a musician strikes an uneasy chord, and goes on to give advice ranging from “court the companionship and respect of dogs,” to “cultivate the arts of dancing and small talk,” and bids them to “continue to give yourself to others because that's the ultimate satisfaction in life - to love, accept, honor and help others.”

And then he begins to walk the walk of a father, arm in arm with his daughter down the aisle of a church, looking over at where she would be he smiles at her, smiles at the imaginary guests … He stops, mails the letter by dropping it into an imaginary mailbox. As moving as his words and actions are to the audience, the three stones are unaffected.

A dubious character in a trench coat, A Nasty Interesting Man, played by Steve Shema, finds the letter Eurydice’s father mailed. He reads it and with an up-to-no-good smirk quickly pockets it.

Wedding day. Eurydice leaves her reception to sit quietly outside and have a drink of water from a well. She is missing her father on this day of days and says, “A wedding is for daughters and fathers. Mothers dress up and try to look young again. But fathers and daughters stop being married to each other on that day.” Just as she’s wondering why there are so few interesting people at her wedding, she’s interrupted by the reappearance of A Nasty Interesting Man.

He is flirty in conversation and demeanor. Eurydice grows suspicious of his motives when he continues his flirtations even after she tells him she has just gotten married. Nasty Interesting Man tells her about the letter. Eurydice doesn’t believe him, naturally, but he insists he has a letter from her father, but not with him. He tells her she must come to his place where he is having a party too, if she wants it. Eurydice goes with him. Once there the Nasty Interesting Man tries to seduce her. When he waves the letter at her Eurydice grabs it and runs out. She doesn’t hear his warning her not to go because she doesn’t know the way out and she might fall or trip on some stairs. Alas, a fall down stone stairs that takes her life.

Orpheus comes looking for her, becomes distraught and returns to the reception while Eurydice arrives in the Underworld (after a dip in the River of Forgetfulness) via an elevator, inside which it is raining as the doors open. She is confused and cannot speak. The Stones explain to the audience it is because she is dead. That she can only speak the language of the dead — which is a very quiet language, “Like if the pores of your face opened up and talked.” When Father arrives and sees Eurydice, she thinks he is a porter come to take her suitcase to her room. He tells her who he is but she cannot remember. This reunion scene tugs at the heartstrings as you watch this father and daughter reunited in death.

“When you were alive, I was your tree,” he tells her taking up the physical pose of a tree, arms outstretched with Eurydice sitting on the ground in front of him, or under his protective “branches.” Blake and D’Arco are fabulous during this time of trying to bring back Eurydice’s memory. Tender moments all around. When Father tells her that he chose her name, he recalls a day when it rained and rained and says, “I heard your name inside the rain--somewhere between the drops--I saw falling letters. Each letter of your name.” Beautifully poetic. Love it.

There are more moments between these characters that audiences will identify with — as both parent and child.

A desperate Orpheus meanwhile writes letters to his beloved bride vowing to find her. Father finds Orpheus’ letter lying where he used to mail letters to Eurydice when she was alive. He reads it, folds it back up and tells her she has a letter. It isn’t until she hears the contents of the letter that she remembers Orpheus. And it is a painful moment of longing and despair.

And then … The Child of Hades, that Prince of the Underworld (also Steve Shema) rides in on a red tricycle dressed in kid clothes of the ’40s to the tune of “Highway to Hell.” Shema’s portrayal of this character is brilliant. Seemingly effortless brilliance. Shema makes every syllable he utters count. He is mischievous, wicked, playful, and wants what he wants (Eurydice) — he is a child man after all.

When Orpheus arrives at the gates of the Underworld his music is so melancholy, so painfully desperate that even the Stones react. Even young Hades is moved to giving Orpheus one chance to be reunited with his love in the Upperworld. “Start walking home,” Hades says. “Your wife just might be on the road behind you. We make it real nice here. So people want to stick around. As you walk, keep your eyes facing front. If you look back at her — poof! She’s gone.”

This Heartwood production is magic. Director Griff Braley described it best: “The script is so delicate. It’s like floating images in the air. Like blowing bubbles. The first scene is a bubble that rises into the air, and then another rises, and another. It’s poetic in that way.”

“Eurydice” opens Thursday, April 27 at 7:30 p.m. and April 28 and 29, May 4-6. For ticket information visit www.heartwoodtheater.org.

Event Date

Address

81 Academy Hill Road

Newcastle, ME 04553

United States