Avian Flu in Maine

Mallards and other waterfowl species that gather in flocks are more susceptible to the spread of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. (Photo courtesy of Jeff Wells)

Mallards and other waterfowl species that gather in flocks are more susceptible to the spread of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. (Photo courtesy of Jeff Wells)

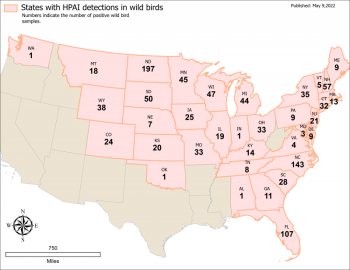

Confirmed detections of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) in wild birds in 2022 as of May 9, 2022 as reported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Confirmed detections of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) in wild birds in 2022 as of May 9, 2022 as reported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Mallards and other waterfowl species that gather in flocks are more susceptible to the spread of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. (Photo courtesy of Jeff Wells)

Mallards and other waterfowl species that gather in flocks are more susceptible to the spread of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. (Photo courtesy of Jeff Wells)

Confirmed detections of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) in wild birds in 2022 as of May 9, 2022 as reported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Confirmed detections of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) in wild birds in 2022 as of May 9, 2022 as reported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

While we humans have been dealing with the difficult and sad implications of COVID, birds have been dealing with a different and very deadly virus called Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI). Avian influenza of various forms has been known to occur in birds for more than a century. It is particularly a problem in commercial poultry operations in which vast numbers of birds are housed in close proximity to each other such that the virus spreads rapidly. The HPAI form is not only highly contagious but also highly lethal. To prevent its spread, all birds in an infected poultry operation must be euthanized and destroyed. Tens of millions of chickens, in particular, have died or been euthanized already this year across the U.S. and parts of southern Canada.

Unfortunately, the virus also has been found in wild migratory waterfowl populations including those of geese, swans, and ducks, which have seen major die-offs in some areas but also in other species like bald eagles, red-tailed hawks, snowy owls, great horned owls, turkey vultures, American crows, common ravens, great black-backed gulls, and herring gulls that may feed on carcasses of birds that have died from the virus.

Many bird rehabilitation facilities in parts of the country where there are major outbreaks of the virus have been forced to stop taking in birds for rescue because of the risk of infecting the birds currently in their care. Facilities that provide long-term care for injured eagles, hawks, and owls have been particularly concerned because those birds have shown susceptibility to the virus.

Fortunately, the HPAI virus does not appear to be of major risk to songbirds or to humans.

The virus has been detected in Maine in poultry flocks and in nine individual wild birds. Six American black ducks were found to have the virus in February in Washington Country. A dead Canada goose found in York County in March and a dead bald eagle there in April both tested positive for the virus and another dead bald eagle from Lincoln County in early April was infected.

As most waterfowl move north and spread out across the breeding grounds and are in less close proximity, the hope is that the virus will have less opportunity to spread and the prevalence of HPAI will greatly decrease. The warmer temperatures of summer are also expected to make the virus less able to survive outside infected birds, which will also make it harder to spread.

Because the virus does not appear to be infecting most birds that frequent bird feeders, there has been conflicting advice about whether to keep feeding wild birds. If you do continue to feed birds, it is always recommended that feeders be thoroughly cleaned regularly and that areas under feeders be kept free of fallen seeds and debris. Other diseases can infect feeder birds like avian conjunctivitis. If you see signs of birds with disease, it is safest to discard the remaining seeds in the feeder, thoroughly clean the feeders, and consider not feeding the birds for several weeks. There’s plenty of available natural food for them so not to worry.

People encountering sick or dead birds in Maine should contact the state veterinarian’s office at (207) 287-7615 or the USDA at 1-866-536-7593.

Jeffrey V. Wells, Ph.D., is a Fellow of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Vice President of Boreal Conservation for National Audubon. Dr. Wells is one of the nation's leading bird experts and conservation biologists and author of the “Birder’s Conservation Handbook.” His grandfather, the late John Chase, was a columnist for the Boothbay Register for many years. Allison Childs Wells, formerly of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, is a senior director at the Natural Resources Council of Maine, a nonprofit membership organization working statewide to protect the nature of Maine. Both are widely published natural history writers and are the authors of the popular books, “Maine’s Favorite Birds” (Tilbury House) and “Birds of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao: A Site and Field Guide,” (Cornell University Press).